Weatherman - The white Black Panthers who tried to revolutionize America with student riots

Born from the ashes of Columbia University 1968 student riots on racial rights, the Weather Underground organization was a radical white movement that sided the Black Panthers and tried to put an end to American society’s imperialism and racism through an attempted revolution.

August 1st 1989, the smoke lifting from a cigarette balanced on a see-through crystal ashtray reaches the ceiling, it’s bounced back and rapidly wraps the room up. The rhythmic clanging of a typewriter stops, two fingers retrieve the cigarette that left to itself had consumed. One last nervous puff, the fingers flick the butt in the ashtray and go back to the typewriter.

Sincerely yours,

Milt Ahlerich

Assistant Director

Office of Public Affairs

The typing stops, and the soft mechanical whir of a desk fan is audible again. Assistant Director Milt Ahlerich nervously opens the office door and hands the letter to his secretary. Despite summertime, the corridors of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, within the U.S. Department of Justice, are buzzing. If New York is the city that never sleeps, Washington D.C. can pride itself of having the most restless offices, while its streets are deserted under the August sun.

The letter is addressed Gui Manganiello, National promotions Director at Priority Records. The message’s urgent matter is the lyrics of a song distributed by the label: N.W.A.’s ‘Fuck Tha Police’.

“Violent crime, a major problem in our country,” writes Ahlerich, “reached an unprecedented high in 1988. Seventy-eight law enforcement officers were feloniously slain in the line of duty during 1988, four more than in 1987. Law enforcement officers dedicate their lives to the protection of our citizens, and recordings such as the one from N.W.A. are both discouraging and degrading to these brave, dedicate officers.”

The letter ends with Ahlerich’s subtle warning about the FBI’s adversity to the song. However, only concern is expressed and no withdrawn of the single is demanded. There’s no need to say that over at the label’s headquarters at 6430 Sunset Boulevard, Hollywood, the U.S. Department of Justice stamp on the letter didn’t make quite of an impression, as proved by the song’s chart success.

On the contrary, Straight Outta Compton – the album containing the song – went beyond Afro American communities and became a generational anthem that cemented white teenagers’ interest in political black music. A song was all it took to N.W.A. to be labeled as public enemies. The group, as much as their contemporaries Public Enemy, in fact made no secret of taking inspiration from the late 1960s Black Panther movement.

Student Juan Gonzalez wears a Black power badge during Columbia occupation, April 1968. Columbia University Archives / Rare Books and Manuscripts.

April 4th 1968, late afternoon warm and weak springtime sun rays seep in through the blinds of a room on the Columbia University campus, New York. The window is closed to soften the noise coming from a nearby building site. “They say they are refurbishing the gymnasium on the campus,” someone told John earlier in the day at the canteen. Surely it is good news, but not for John. In fact, they are building two entrances, one on the upper north side for the students, one on the back for the residents of the nearby neighbourhood of Morningside Heights, mostly populated by Afro Americans. John is finding it hard to focus on his typewriter. The noise, another excuse to perpetrate class division, the revision books piled up, the articles left unfinished. John turns the radio volume up in an attempt to cover both the drilling and his fragmented thoughts.

He’s trying to follow the steps of his father Robert. Robert Jacobs, the well-known leftist journalist who had made a name for himself covering the Spanish Civil War some twenty years earlier. John’s temper and political knowledge have already gained him a prominent role in Columbia’s branch of activist group SDS (Students for a Democratic Society). Born in the late 1950s within the frat houses of Ann Arbor campus, Michigan University, the SDS held together several factions of left-wing student activist groups. They could be seen as a politicised evolution of 1950s beatniks filtered through 1960s psychedelic, pacifist, feminist and anti-nuke culture. A generation of angry young American men inspired by John Baez’s ‘We Shall Overcome’ and by the British CND, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

It’s nearly 6 p.m., the day is unfolding unproductively, and the construction works have stopped for a while now. John is called back to reality by the radio’s loudness breaking through the late afternoon quiet. “You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows,” Bob Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ is playing. John remembered how just three years before Dylan was booed at the Newport Folk Festival when he walked on stage with an electric line-up, also featuring Mike Bloomfield on guitar and two Afro American musicians from the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay.

SDS and SAS students occupy Columbia University buildings, April 1968. Don Hogan Charles / The New York Times / Redux

Some say Dylan had done it to prove something to festival organiser Alan Lomax, who’d previously expressed his skepticism on an electric blues band in a festival of folk purists. John knew that wasn’t racism, at least not from the student crowd. Some people were saying that the tensions between Dylan and the festival board had started when earlier in the afternoon the singer wouldn’t give up rehearsing when the stage was needed for a vocal group of ex-convicts, who had been recruited to sing prison work songs.

John knew that the music business was as intricate as politics. It was all about conservatives and progressives, back-stabbing, press statemets, and violence too. Then a buzz, the music is interrupted. It’s a breaking news update from Dallas. Dr. King has been shot.

It’s confusion at first, disbelief, and then anger. It’s just a matter of hours before Harlem is set on fire by riots. John spends the night wondering through those streets, inspired and excited by the revolt. Tension rapidly escalates outside of Harlem too, up to Columbia University where by April 23rd the SDS has organised a march led by Jacobs. The occupation of university halls begins, inevitably followed by police repression.

Within a handful of days, the 300 SDS activists are joined by 1,000 more Columbia students including SAS (Students Afroamerican Society). Pan-African movement activists Stokley Charmichael and H. Rap Brown come in aid, armed militants from Harlem take neoclassical building Hamilton Hall that is re-named ‘Malcolm X University’, and civil rights lawyers are called in to make sure Afro American activists are treated fairly by the NYPD. Jacobs, inspired by French revolutionary George Danton’s motto ‘Audacity, audacity, and more audacity,’ leads the seizure of the Law Memorial Library and the Mathematics Hall. One of the establishment of Ivy, white, middle-class education is now facing the anger of America’s changing face.

Left: Students protest on the occupied Columbia University campus, April 1968. David Finck.

Below: Protesters march in Morningside Park where the gymnasium was being built. Hugh Rogers

SAS activists joined the student protest. Richard Howard

As student and SDS member Susan Biberman recalls: “Two strands of anger and disgust converged: what the university was doing to aid the war effort, and what [it] was doing that was racist in our neighborhood.”

The occupied buildings are turned into communes for the weeks to follow. Students and SDS members hold seminars on the themes of racism and imperialism. New York is living its own 1968 student riots, with the difference that these are moved by more pressing matters: racism and the Vietnam War. Jacobs, a born leader, comes up with the slogan that will echo throughout hundreds of students protests, ‘Bring the War Home’.

New York mayor, the Republican John Linsday, is resolute in ending the occupation drastically. Snipers are sent on campus, ready to shoot on the activists. John, though, has a spark of genius, one of the many intuitions that for years will keep him free from handcuffs. He orders to seize Columbia’s precious collection of Ming Dynasty vases and place them on the Mathematics Hall’s windowsills. Coup de theatre, the cops can’t shoot to make their way into the building.

By the end of the month, on April 30th, though, NYPD squads manage to break in two of the occupied buildings with the aid of tear gas and put an end to the protest. If Afro American militants are peacefully escorted out of the campus thanks to the presence of their lawyers and the tactical use of black officers. Law enforcement is less lenient with white SDS students who are charged and beaten up with batons.

Above: Poster for SDS/Weatherman ‘Days of Rage’ demonstration in Chicago, October 1969.

Right: The Weather Underground Organization logo

Over the following months, Jacob’s radicalisation augments to the point that the SDS’ manifesto and modus operandi are deemed too weak to tackle imperialism and racism. The fracture within the movement is inevitable.

‘You Don't Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows’ reads the title of an article signed by Jacobs and published on the SDS’ paper The New Left on June 1969, just in time for the movement’s Chicago convention starting on the 18th. The gazettes are being handed out by a group of students wearing black leather jackets, motorbike boots, and black turtleneck jumpers. Some of them have dark sunglasses, some sport a shirt over the turtleneck in the fashion of psychedelic groups, just like The Seeds. You would assume they belonged to the Black Panthers, if it only wasn’t for their white skin. At a closer look, one would say they are a peculiar crossover between the Panthers and the biker gang captured in 1966 film The Wild Angels. The Black Panthers, though, are attending the convention too, in support of newborn SDS’ Jacobs-led faction Weather Underground Organization, or simply Weatherman. If the SDS could be associated to the early 1960s folk of Baez and Seeger, the Weatherman are the political and armed face of Detroit militant musicians MC5’s raw soulful garage rock.

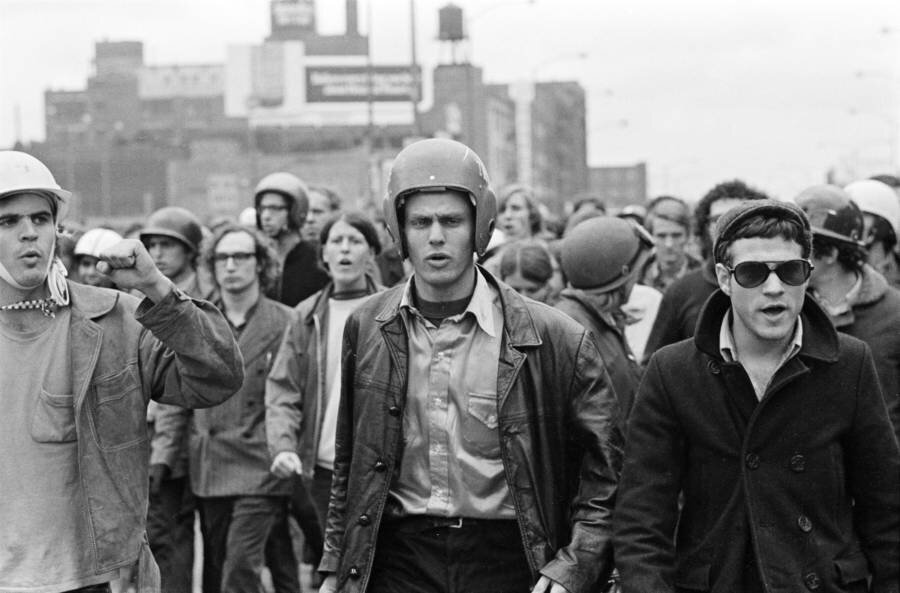

Weatherman’s distinctive helmets at the Days of Rage, Chicago, October 1969. David Fenton / Getty Images

Motivated by ‘The Elections Don't Mean Shit—Vote Where the Power Is—Our Power Is In The Street’ motto, the Weatherman turn into a white revolutionary group affiliated to the Black Panthers. Jacobs’ and associates are determined to put an end to Nixon government’s imperialism and racism even at the cost of their own lives. Replacing Black panthers’ iconic berets with motorbike, football, army and builder helmets, the Weatherman pour their anger into a national demonstration known as ‘Four Days of Rage’ held in Chicago in October 1969.

Inspired by Lenin’s theory of turning imperialist wars into civil wars, the Weatherman bomb a statue commemorating fallen policemen and stepping on its basement declare war to the United States.

By the end of the decade, though, revolutionary movements are no immune to the drug-fueled self-destructive paranoia that creeps throughout countercultural environments. If the tragedy occurred at the Rolling Stones’ Altamont concert is often referred to as the paradigm of the end of the hippy dream, the inglorious end of the Weatherman could set another standard.

John Jacobs leads the Weatherman march in the Days of Rage, Chicago, October 1969. David Fenton / Getty Images

In March 1970 the movement’s board moved into a New York Greenwich Village townhouse owned by the dad of activist Cathy Wilkerson. Whilst the group is putting together a bomb to attack a political target, the rudimentary device blows the house up killing three of the Weatherman and partially damaging neighbour Dustin Hoffman’s house. Hilarious, if it wasn’t that tragic, how Weather(wo)man Kathy Boudin has to flee the house naked because surprised by the explosion in the shower.

Jacobs, who isn’t on the premises, manages to survive and will start living a life on the run, chased by the FBI after the U.S. government had classified the Weather Underground Organization as a terrorist group.

Dustin Hoffman fleeing his partially blown up flat. Frank Castoral/ NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images

Despite the irresolute ending of the organization, Jacobs and the Weatherman stand out as one of the first examples of solidarity on the theme of racism that, although characterised by a conspicuous dose of 1960s political naivety, looked beyond ethnicity. As the Columbia University riots show, real history - that happening on the streets rather than on textbooks –is never made of perfectly neat contrasts but it is rich in shades and exceptions that often lie forgotten, just like this story. The Columbia student riots and Weather Underground Organization’s legacy, though, stands the test of time because never as much as today the youth is facing the same epochal generational gap 1960s teenagers lived.